Correlation is not causation

During the last 30 years, classical epidemiology has focussed on the control of confounding [1]. However, it is only recently that epidemiologists have started to focus on the bias produced by colliders and mediators in addition to confounders [2, 3]. In the epidemiological literature different explanations have been proposed to describe the paradoxical protective effect of established risk factors. Such as, for example, the protective effect of maternal smoking on infant mortality and the incidence of pre-eclampsia, namely the birth weight and the smoking pre-eclampsia paradoxes [4, 5].

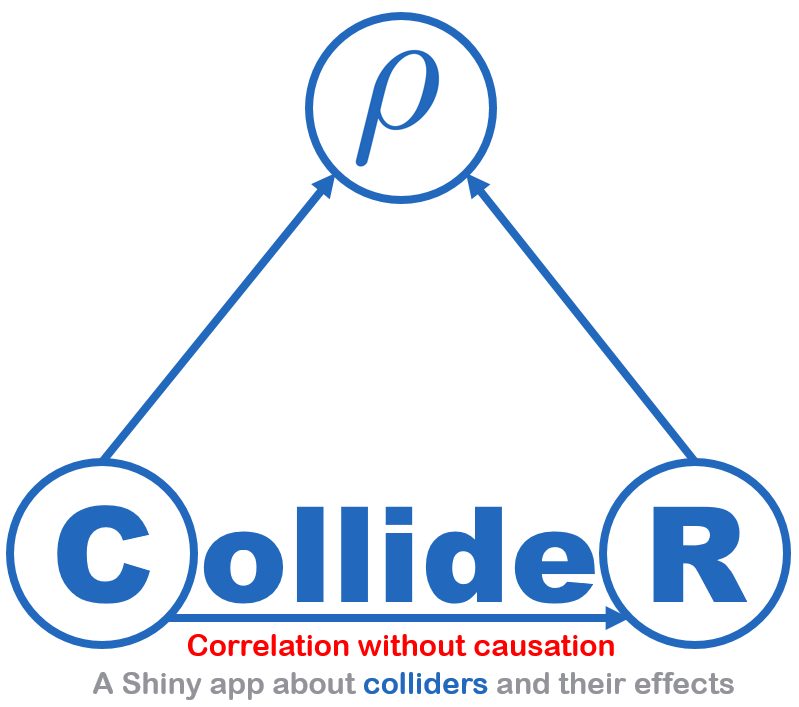

What is a collider?

A collider for a certain pair of variables (outcome and exposure) is a third variable that is influenced by both of them. Controlling for, or conditioning the analysis on (i.e., stratification or regression) a collider, can introduce a spurious association between its causes (exposure and outcome) potentially explaining why the medical literature is full of paradoxical findings [6]. In DAG terminology, a collider is the variable in the middle of an inverted fork (i.e., variable W in A -> W <- Y) [7]. While this methodological note will not close the vexing gap between correlation and causation, but it will contribute to the increasing awareness and the general understanding of colliders among applied epidemiologists and medical researchers.

Objective

To illustrate with an educational purpose the effect of conditioning on a collider based on a realistic non-communicable disease epidemiology example (hypertension and dietary sodium intake). We estimate the effect of 24-hour dietary sodium intake in grams (exposure) on systolic blood pressure (outcome) accounting for the effect of age (confounder). The objective of the illustration is to show the paradoxical effect of 24-hour dietary sodium intake on systolic blood pressure after conditioning on 24-hour excretion of urinary protein (collider).

Link to the web application

http://watzilei.com/shiny/collider/

References

[1] Sander Greenland and Hal Morgenstern. Confounding in health research. Annual Review of Public Health, 22(1):189-212, May 2001.

[2] Stephen R Cole, RobertWPlatt, Enrique F Schisterman, Haitao Chu, Daniel Westreich, David Richardson, and Charles Poole. Illustrating bias due to conditioning on a collider. International Journal of Epidemiology, 39(2):417-420, Nov 2009.

[3] Tyler J. Vanderweele and Stijn Vansteelandt. Conceptual issues concerning mediation, interventions and composition. Statistics and Its Interface, 2(4):457-468, 2009.

[4] Miguel Angel Luque-Fernandez, Helga Zoega, Unnur Valdimarsdottir, and Michelle A. Williams. Deconstructing the smoking-preeclampsia paradox through a counterfactual framework. European Journal of Epidemiology, 31(6):613-623, Jun 2016.

[5] S. Hernandez-Diaz, E. F. Schisterman, and M. A. Hernan. The birth weight “paradox” uncovered? American Journal of Epidemiology, 164(11):1115-1120, Sep 2006.

[6] Julia M Rohrer. Thinking clearly about correlations and causation: Graphical causal models for observational data. 2017.

[7] Judea Pearl. Causal diagrams for empirical research. Biometrika, 82(4):669-688, 1995.

MA Luque-Fernandez & Daniel Redondo

MA Luque-Fernandez & Daniel Redondo